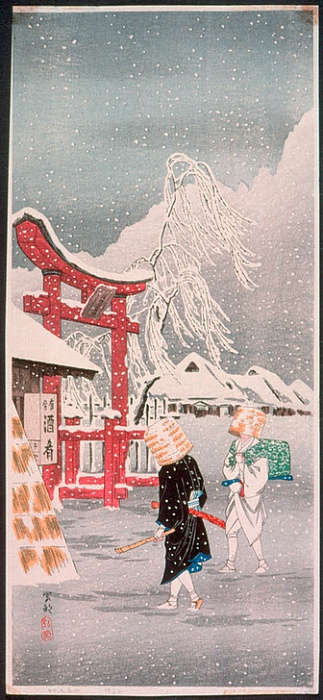

Komuso Shakuhachi Monks

Woodblock print by Takahashi Hiroaki, c. 1935

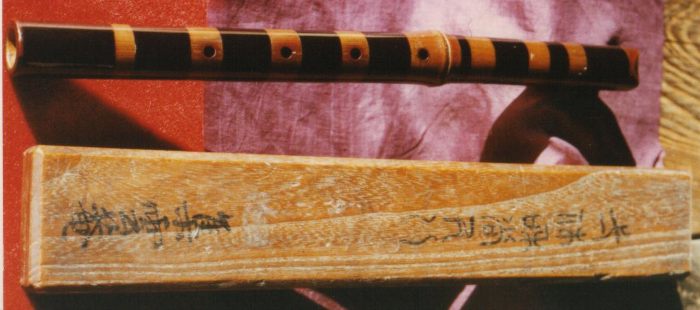

Ikkyu Sojun

Ikkyu Sojun and his shakuhachi

Ikkyu Sojun 一休宗純 (1394–1481) perhaps needs little introduction as he is one of history's most well known Zen Buddhist figures. Ikkyu particularly loved playing shakuhachi and composed poems about it. In Volume 1 of the Shorin Mukuteki, a passage from Toyo Eicho recounts how he witnessed Ikkyu Sojun playing the shakuhachi in the Zen temple Daitoku-ji in Kyoto in late 1474, when Ikkyu entered the Abbot's Quarters of the temple to become its rebuilder and restorer.

Toyo Eicho writes:

不寒臘後

看一休和尚

入牌祖堂正宗滅却。

- - -

狂雲吹起寶山巓。

"In the not cold Winter, after the offering ceremony held on the third Day of the Dog after the Winter solstice [12th month, 1474], I saw Abbot Ikkyu as he entered beneath the sign board of the Founder's Hall [of Daitoku Temple in Kyoto] after its destruction [in the Onin War, 1467-1477].

- - -

Kyoun [Ikkyu's literary name] blew forth [on the shakuhachi the tune] Hosanten, Summit of the Treasure Mountain."

On that day, Ikkyu also recited a poem attributed to Zhenzhou Puhua or Fuke Zenji 鎮州普化/普化, titled Myoan 明暗 (more on Fuke and the Fuke Shu further down below).

明暗 - Myoan, by Fuke Zenji (recited by Ikkyu Sojun)

普化和尚

議論明頭又暗頭

老禅作略*使人愁

古往今耒風顛漢

宗門年代一風流

The monk P'u-K'o.

Arguing first at the Bright Head, then the Dark,

That Zen-fellow's tricks fooled them all.

Now, blowing up again, the same old madman,

A sensual youth, howling at the door.

Ikkyu Sojun, 1394-1481. Poems in the 'Kyōun-shū'. Trsl. by James H. Sanford, 1981.

More poems attributed to Ikkyu Shojun which mention the shakuhachi

なかなかに

われに如かざる

人よりも

只尺八の

声ぞ友なる

Very much so it is for me

that even compared to the very best person

only the voice of the shakuhachi is really a friend.

尺八は

ひとよばかりと

思いしに

いくよか老いの

友となりぬる

In just one evening

the shakuhachi made me realize

that for numerous nights to come

it has become like an old friend.

Transl. by Torsten Mukuteki Olafsson, 2010. Source: Nakatsuka, 1979, p. 66.

The Rural Monk in Uji

尺八

因憶宇治庵主曽

餒膓無酒冷於氷

明皇天上羽衣曲

偶落人間慰野僧

Shakuhachi

Even now I remember the recluse of Uji.

Empty belly, no wine, colder than ice.

Yet, that song of the angel's shining cloak.

Lost among refugees, the rural priest takes comfort.

Ikkyu Sojun, 1394-1481. Poem in the 'Kyoun-shu'. Trsl. by James H. Sanford, 1981.

In short, Ikkyu Sojun was the first prominent figure in Buddhism to play the shakuhachi. There's little doubt that he influenced future generations of shakuhachi players, including the predecessors to the Komuso, the Komoso.

The Komoso

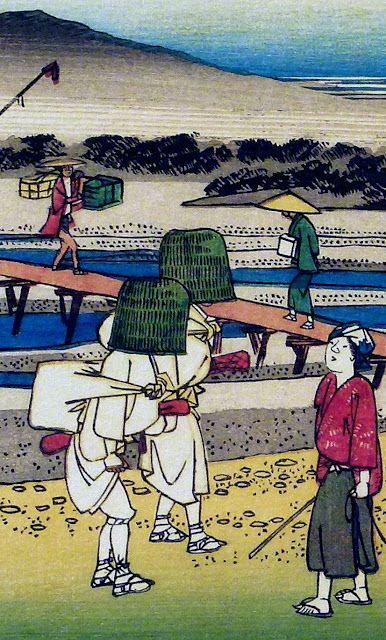

Non-Samurai Komoso 'straw mat monk' playing shakuhachi - 'Sanjuni-ban Shokunin', 16th c., Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo Japan

In mid 15th century literature we began to see mentions of shakuhachi playing 'beggar monks' called Komoso or 'straw mat monks' 薦僧/菰僧. Their name comes from the fact that they carried straw mats around with them to sleep on or to use as shelter from the elements. The Komoso would play shakuhachi for alms or donations, however, they were mostly laypersons of 'commoner' birth. In Japanese, the word for Buddhist alms begging is Takuhatsu (often pronounced Takahatsu).

Uchiyama Kosho Roshi (1912-1998) wrote, "The attitude of one on takuhatsu must be one of equanimity, whether no donation is received or a large one is received. In fact, the attitude of the mendicant on takuhatsu is one of giving an opportunity to people to materially support a life of one dedicated to zazen and the teaching of the Buddhadharma."

As for their shakuhachi, the root end of the bamboo hadn't come into use yet, as we saw previously with Ikkyu's shakuhachi. Thus, the shakuhachi of the Komoso were crafted from 'above root' or 'non-root' bamboo. Shakuhachi were also shorter around 1.08 in length or ichi-shaku-hachi-bu (32.7cm/12.8in); 22cm shorter than the later and current standard of 1.8 or ichi-shaku-hachi-sun (54.5cm/21.5in).

The shakuhachi would also see other variations and evolutions before reaching the root end form we're familiar with today (the root end did not come into use until nearly one thousand years after the arrival of the first shakuhachi in Japan, 8th c. to late 17th c.).

Komoso to Komuso

Ronin Samurai turned Komoso playing 'above root' shakuhachi

Kasa hari and Komuso zu 傘張り•虚無僧図 - by Iwasa Matabei, c. 1630

In the latter half of the 16th century an increasing number of Samurai found themselves ronin or 'masterless'. As a result, many more of these ronin Samurai began joining the ranks of the shakuhachi playing Komoso. In the mid 16th century, the Komoso became associated with the legendary Chinese Chan Buddhist sage Fuke Zenji (Japanese pronunciation). It's speculated that this association was made in order to establish a Chan/Zen lineage in order to gain legitimacy for the group.

In the legends, Fuke Zenji would ring a small handbell for the purpose of teaching or 'showing' the 'Dharma'. It's thought that the Komoso were trying to make a connection between the bell of Fuke Zenji and their shakuhachi, in other words, the use of a 'sound device' for spiritual Buddhist purposes. As such, in some texts the Komoso were additionally referred to as Fuke so or 'Fuke monks'. However, it's unclear whether these associations with Fuke Zenji were being drawn by 'commoners' or the 'nobleman' ronin Samurai-turned-Komoso.

Eventually, the Samurai began calling themselves the Komuso or 'illusory nothingness monks' 虚無僧. As such, the 'commoner class' Komoso begin to disappear from history as the 'nobleman' Samurai Komuso and the Fuke Shu sect grew. The Fuke Shu tried make the act of playing shakuhachi for alms exclusive to the Komuso, and thus prohibited for non-Komuso 'commoners' to do so. Note that neither the Komoso nor the Komuso and their Fuke Shu Buddhist sect was ever officially recognized by the Japanese government or any of the established Buddhist sects.

Furthermore, the Komuso claimed that the founder of the Fuke Shu was a one Roan, and that he was a friend of Ikkyu Sojun's. However, historians have largely determined Roan to be a fabrication. With that said, this seems to clearly reveal that the writings and stories of Ikkyu Sojun and his shakuhachi inspired some of the early Komuso monks.

The Komuso of the Fuke Shu would go on to establish a network of temples, most notably the temples of Myoanji in Kyoto and Ichigetsuji in Edo, aka Tokyo. The Komuso had to relinquish their Katana, but they could carry a Wakizashi or 'shortsword', however, this too was also eventually prohibited. They also began making shakuhachi from the root end of the bamboo, most likely during the 1700's, and they extended the standard length by roughly 22cm; from 1.08 to 1.8 shaku.

Komuso Spirituality

Honkyoku 本曲, the most venerated pieces of shakuhachi music, were primarily composed by anonymous Komuso monks and are considered to be spiritual, often as Buddhist or Shinto inspired meditations and/or liturgy. The 'genre' is thought to have originated from the Southern island of Kyushu, Japan.

The word Honkyoku can refer to a single piece or to the genre as a whole. The Kanji for Hon 本 can mean 'main/original/true/real', while Kyoku 曲 can be taken as, 'piece/composition/music'. Distinct regional styles developed across Edo period Japan, and while many Honkyoku are thought to have been lost, the surviving pieces comprise the largest body of solo wind instrument music in the entire world.

Honkyoku often have titles and themes inspired by the aforementioned religions of Japan. In fact, the Samurai who became Komuso shakuhachi playing monks practiced all of these religions, to varying degrees. Therefore, they inevitably brought over elements from these religions to shakuhachi.

In Shinto, for example, the deer is considered a sacred animal and in some cases a messenger of divinity. For Japanese people, the Kinko Ryu Honkyoku piece Shika no Tone or 'Distant Cry of the Deer' can both reflect nature, as it is, in a Zen sense, as well as the sacred status of the deer in Shinto. Furthermore, the Honkyoku piece Ajikan takes its title from a Shingon Pure Land Buddhist meditation practice in which the 'object' or 'focus' of the meditation is the Sanskrit syllable Ah, i.e.,Ah and Om.

Additionally, the Honkyoku titled Koku 虚空 or 'Empty sky' is understood as alluding to our 'true nature', as expressed in Zen. In this context, 'empty sky' is more so understood as the potential for anything; 'empty' of a permanent or static state. A cloud passes through the sky just like things pass through our senses. Both the sky and the senses have no inherent will. This is sometimes also likened to a mirror which simply reflects.

The Tengai Basket Hat and Other Komuso Vestments

Kisokaido Road, Echikawa - by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

The Tengai 天蓋 or 'heaven cover' hat is perhaps the most iconic Komuso item next to the shakuhachi. Like the shakuhachi, it saw an evolution, from generic straw hat to the iconic 'beehive' like shape which fully incases the head. It’s been said that its final form was a tool to aid in the suppression of the ego, as well as a means to help people to listen to the shakuhachi, rather than being concerned with the identity or emotions of the Komuso.

It's also been speculated that it provided a disguise and/or a way to hide exactly how the shakuhachi was being played. The Tengai hat is typically woven from either grass reed, rattan, or even bamboo. It also has a unique headband 'suspension system' which is secured with string which allows the hat to move with the motions of the player.

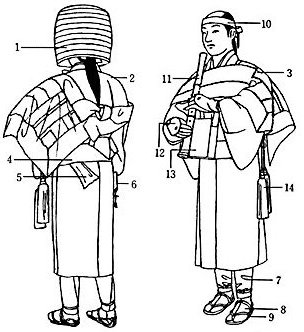

Diagram of Komuso vestments (unknown origin)

(Note that the 'shortsword' or Wakizashi is not included in this most likely modern diagram)

1. Tengai (天蓋) - basket hat; ten 'sky/heaven'; gai 'cover'

2. Kimono (紋付) – usually montsuki 'five crest'

3. O'kuwara (大掛絡) – like Zen Rakusu except larger and worn over the shoulder

4. Obi or Kaku-obi (帯) – a stiff cotton belt

5. 2nd shakuhachi (usually fake these days)

6. Netsuke (根付) – place to store small items

7. Kyahan (脚半) - shin covers

8. Tabi (足袋) - split toe socks

9. Waraji (草鞋) - straw sandals

10. Hachimaki (鉢巻) - head band

11. Shakuhachi (尺八) - 1.8 'D/Db' ichi-shaku-hachi-sun

12. Teko (手甲) - hand and forearm covers

13. Gebako (偈箱) - 'alms box' which could also hold the Kai in or 'official documents'

14. Fusa (房) - tassel

Initiation of a Komuso

To become a Komuso of the Fuke Shu during the Edo period, one had to produce their papers of Samurai lineage, pay an entrance fee, and take oaths. The new Komuso would be given the San gu or 'three tools' and the San in or 'three seals'. The 'three tools' were the shakuhachi, the Tengai, and the O'kuwara 'shawl' (Rakusu/kesa). The O'kuwara shawl is much like the Zen Buddhist Rakusu, however, the Komuso O'kuwara is larger and worn over the shoulder, instead of in the regular position in front of the body.

The San in were the Honsoku 'Komuso license' to beg, the Kai in or 'personal identification papers', and the Tsu in document which allowed them to cross borders. They were also given a Gebako which is a lacquered wooden alms box or cloth bag worn about the neck in which were stored the official papers. Some Komuso also received their alms in the Gebako box.

Activities of the Komuso

The chief activity of most Komuso would have been playing Honkyoku. Generally, a Komuso would beg for alms by playing a Honkyoku outside of a home, place of business, or in town. However, some Komuso were known to have practiced near extortion in order to receive alms by intimidating people, loitering, and causing 'noise'. Additionally, some Komuso would play shakuhachi for auspicious events, such as funerals, and received alms for their services.

Perhaps most notably, Komuso could wander far and wide across Japan. For instance, it's well known that Komuso traveled to other Fuke Shu temples where different regional Honkyoku styles had developed. In turn, this allowed for some 'cross-pollination' of these regional Honkyoku styles. For example, the famous Komuso Kurosawa Kinko I (1710-1771) collected various regional Honkyoku across Edo period Japan. His collection was posthumously codified into the Kinko Ryu school, which survives to the present day.

Shakuhachi as a weapon

We'll never know to what extent or how often the shakuhachi was used as a weapon during the Edo period and earlier. However, what we should call into question are those who still perpetuate fantasies of bloodshed, especially without condemning violence, all in order to tantalize at the expense of the greater artistic and spiritual legacy of the Komuso monks and their direct descendants.

Teaching of Laypersons and the Evolution to Modern-day Instruction

The Fuke Shu attempted to keep the shakuhachi exclusive to the Komuso, however, many laypersons or 'non-Komuso' continued to play the shakuhachi. Over time, these 'non-Komuso' lay shakuhachi players became a part of Sankyoku secular ensemble music with Koto and the Shamisen. Near the end of the Edo period, the Fuke Shu actually began to allow Komuso to teach shakuhachi to laypersons for a fee. These students could also earn shakuhachi playing licenses and professional titles.The Banning of the Komuso – The Meiji Restoration and the Dissolution of the Fuke Shu

It's estimated by some that there were more than one hundred Komuso shakuhachi temples across Edo period Japan. However, the Meiji Restoration (1868 - 1889) abolished Buddhism which resulted in the closing, converting, or more often, the destruction of the Komuso temples. In fact, the new Meiji government soon decided to ban shakuhachi playing altogether, however, the Kinko Ryu Grandmasters Araki Kodo II (Chikuo I) and Yoshida Ittcho successfully petitioned the new government to allow secular shakuhachi music to continue.

Despite these challenges, the traditions of the Komuso persist into the modern era, though the Fuke Shu was never officially restored. Today, there are those who carry on the practices of the Komuso, primarily via the preservation of the Honkyoku. In conclusion, the history of the Komuso is a testament to the enduring power of spiritual and artistic practices in the face of adversity. Despite persecution and many other hardships, the Komuso remained committed to their shakuhachi practice, inspiring generations of players.